Fifty years ago, the law we now call the Bank Secrecy Act (BSA) was passed, and the war on financial crimes truly began.

The BSA began with the Currency and Foreign Transactions Reporting Act of 1970. In the years that followed, several laws and statutes solidified BSA regulations, and American historical events heightened the necessity for effective financial crime management. While there have been many notable dates and events, there are several truly defining moments in the long and storied history of the BSA.

What is a “defining moment?” A defining moment is an external event that (1) we weren’t prepared for or had not anticipated, (2) changed the way society behaved, and (3) resulted in legislative changes that had previously been politically impossible.

Several such defining moments have shaped the American war on financial crimes. Here, I will explore how the 9/11 terrorist attacks and the financial crisis of 2008 changed the BSA/AML landscape. I will also discuss how, as we move forward, the current COVID-19 pandemic may be counted among those milestones for its significant impact on financial crime management and the industry as a whole.

The Terrorist Attacks of September 11, 2001

In the years before 9/11, regulators had proposed Know Your Customer (KYC) regulations for financial institutions. The public pushed back, and even the Comptroller of the Currency eventually testified before Congress that the proposed regulations went too far. While multiple bills were introduced in Congress to address international money laundering, foreign anti-corruption, and to include new financial sector actors in the BSA/AML regime, these bills never became law.

But within 45 days following the 9/11 terrorist attacks — during which Congress was shut down because of the anthrax crisis — the House and Senate crafted what became known as the USA PATRIOT Act. It was a blend and compromise of the Senate’s Uniting and Strengthening America (USA) Act and the House’s Providing Appropriate Tools Required to Intercept and Obstruct Terrorism (PATRIOT) Act.

The USA PATRIOT Act has ten titles. Title III, the “International Money Laundering Abatement and Anti-Terrorist Financing Act of 2001” includes much of what had been in the International Counter-Money Laundering and Foreign Anticorruption Act of 2000. And the centerpiece of Title III? The previously rejected KYC, which had evolved into even stricter Customer Identification Program (CIP) and Customer Due Diligence (CDD) requirements. The new CIP and CDD provisions of USA PATRIOT Act went well beyond what had been proposed, and rejected, in the years prior.

With the defining moment of 9/11, what had been too much became not enough: the results were new financial crimes legislation and regulations, new federal agencies such as the Department of Homeland Security, and the way we traveled was forever changed.

The Financial Crisis of 2008

The 2008 financial crisis actually ran from early 2007 to early 2009: in February 2007, Freddie Mac and Fannie Mae stopped buying subprime mortgages; in September 2008, Lehman Brothers collapsed; and by February 2009, the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act had been passed.

During this two-year period another profound shift was occurring. A technology revolution introduced cloud computing, big data, the smartphone, and virtual currencies.

The 2008 financial crisis resulted in new legislation such as Dodd-Frank, new federal agencies such as the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, and new fintech firms providing financial services. In the years following the 2008 financial crisis, we saw the rise of artificial intelligence and machine learning, and the way in which we banked and how we managed the risks of financial crimes was forever changed.

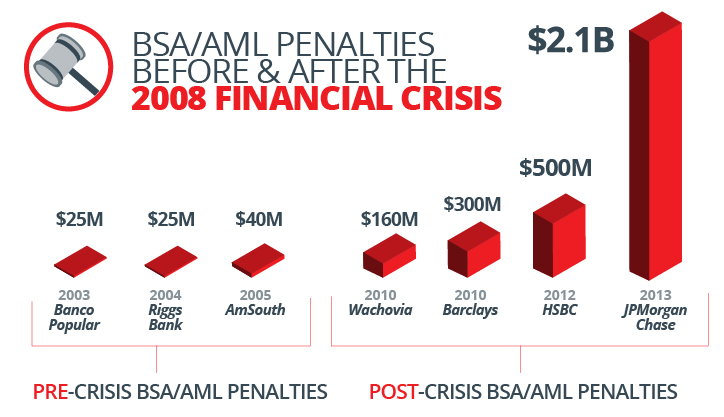

But coming out of that financial crisis, before all these technology advancements could positively impact us, regulators heightened their expectations and their penalties for failing to meet those expectations. Regulations were updated in two new editions of the FFIEC BSA/AML Examination Manual – the first published in 2010, and the second in 2014. Penalties resulting from these new regulations were significantly higher than earlier fines.

Notable pre- and post-crisis penalties include:

| Pre-Crisis BSA/AML Penalties | Post-Crisis BSA/AML Penalties |

| 2003 Banco Popular $25 million 2004 Riggs Bank $25 million 2005 AmSouth $40 million |

2010 Wachovia $160 million 2010 Barclays $300 million 2012 HSBC $500 million 2013 JPMorgan Chase $2.1 billion |

These post-crisis penalties don’t include the OFAC “stripping” cases, where ten foreign banks paid over $12 billion in fines and penalties for violating OFAC-related laws.

2015 saw the beginning of a period of responsible innovation and collaboration. Regulatory agencies and FinCEN were actively encouraging financial institutions — and their fintech partners — to use innovative new technologies to embrace the notion of sharing information. With cloud computing technology, institutions could now engage in collaborative investigations. But at the same time, expectations for running effective programs, and penalties for failing to run effective programs, remained high: from January 2015 to the end of 2019, there were 28 financial crimes-related fines and penalties of $5 million or more, totaling more than $10 billion.

The Global COVID-19 Pandemic

The COVID-19 crisis is unlike anything we’ve seen before. While the world has faced other health crises in recent years, such as the SARS epidemic of 2002-2004 and the West African Ebola epidemic of 2013-2016, the COVID-19 pandemic has spread rapidly across the globe and has impacted all aspects of society. Governments, financial institutions, and individuals have had to quickly respond to the threat of COVID-19, as the pandemic continues to impact the way we live, work and travel.

Most Americans have been under shelter-in-place orders and have been working from home since March. The unemployment rate has skyrocketed to Great Depression levels and it is hard to fathom a path forward.

We are only now beginning to understand the risks and repercussions of this global pandemic.

The disruption to the American and global economies has highlighted if, and how, the financial industry was prepared to handle this crisis. While the pandemic compelled financial institutions to adopt new business-as-usual processes, these changes have caused challenges for fraud, AML and compliance programs at institutions of all asset sizes. The ability of institutions to adapt to this evolving situation depends on their size, complexity and preparedness.

The way money moves through the financial system changed seemingly overnight, as digital banking now dominates. Changing customer behaviors forced financial crime management programs to rapidly respond and adapt transaction monitoring to ensure a balance of providing access to financial services, while mitigating the risk of money laundering and fraud.

New laws, such as the CARES Act and the Paycheck Protection Program Flexibility Act (PPPFA) have been signed faster than ever before. With over $2.4 trillion being pumped into the economy through stimulus payments, and unemployment insurance benefits claims soaring, the volume and value of financial aid making its way through financial institutions, destined for businesses and individuals in need, is clearly historic.

Without fail, the criminal element too has responded to the crisis. Fraudsters and criminal networks adapted quickly, preying on the fear and turmoil caused by the COVID-19 pandemic to garner illicit funds — from fraud scams targeting vulnerable persons, rerouting aid and benefit payments, to organized crime ring activity spanning multiple institutions.

It’s fair to suggest that we are in the midst of the third defining moment of combating financial crimes.

Looking Forward

We are now in the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic. Like defining moments from the past, this global health and economic crisis may result in new legislation, more regulations, and perhaps even new federal agencies. At a minimum, the COVID-19 pandemic will change the way we travel, the way we bank, and the way we work.

But exactly what will those changes be? And how will they impact financial crimes risk management?

As Yogi Berra once said, “it’s tough to make predictions, especially about the future.” He also said, “the future isn’t what it used to be,” and that’s so very true today as we all struggle through the COVID-19 crisis in our own personal ways.

Financial institutions must remain steadfast in their BSA/AML reporting obligations during this challenging time. While the impacts of this defining moment are unknown, FinCEN has stated that “Information sharing among financial institutions is critical to identifying, reporting, and preventing evolving fraud schemes, including those related to COVID-19,” reiterating that “Financial institutions sharing information under the safe harbor authorized by section 314(b) of the USA PATRIOT Act…may share information relating to transactions that the institution suspects may involve the proceeds of one or more specified unlawful activities (“SUAs”) and such an institution will still remain protected from civil liability under the section 314(b) safe harbor.”

Only time will tell what the ramifications of the pandemic will be long-term for financial crime management programs, and what legislative or regulatory changes may arise from this crisis. This defining moment in the war on financial crime certainly has, and will, continue to impact the way in which financial institutions prepare for change, provide service to customers, and protect the financial system from illicit activity.